When my kids were small they loved reading board books. A family favorite was the classic text called “Caps for Sale” about a person selling caps who, on a slow day, decides to take a nap under a tree. The cap seller wakes up to find each of his caps on the heads of a dozen or so monkeys in the branches overhead. Needless to say, this does not go over well with the cap seller.

The man demands the monkeys return his caps, and wields his fists while shouting loudly: give me back my caps! As one would guess, the monkeys don’t quite speak human, so instead of kindly responding, the monkeys simply copy the man’s hand motions thus making the man even more furious. A classic case of monkey see, monkey do. Or is it?

All of this was great fun to my children, who squealed with delight as I’d shake my fists playfully while acting as the cap seller saying: tsk tsk tsk! But what I realized on the second (or perhaps fortieth) read was how completely oblivious the cap seller is to why the monkeys were seemingly mocking him: the troupe of monkeys did not speak the man’s language.

While I can’t recall the day my children stopped reaching for that board book, I’ll never forget the powerful realization that so much of our communication is literally lost in translation. What’s more, we all wear many hats, and the way we communicate changes depending on the hat we’re wearing.

As a mom, I am often silly, sometimes stern, and always ready for a hug. As a professor, I aim to provide prompt but pithy just-in-time support with enough compassion to let my students know I care deeply and respect their time. As a school board member, I try to model thoughtful questioning and active listening, although I sometimes pull from the playful “mom” behavior to bring levity and grounding to our heavier conversations.

As educators, we know that behavior IS communication! And oftentimes, breaking the barriers of language or culture (or species?) is best done by meeting others where they are, through the lowest stakes possible. When it comes to our kids it’s often through play.

When the schools closed down in March, it was devastating to watch as our children suffered from the missed human connection. But the moment they hopped on to Fortnite, it was as if their entire ‘squad’ of friends magically descended upon our living room as I heard excited talking, connecting, and my most favorite sound of all: laughter.

My hope in writing Game On? Brain On! is not simply to share the earth-shattering insight that we all learn best through play. Every good educator knows that! Instead, my goal is to share the many ways that play taps into the best that learning science has to offer and then turn to the experts, our educators, and ask: where can we infuse more playful and perhaps more compassionate learning into our work together?

Learning looks differently right now and all bets are off, but there are some constants that can both ground your work online or in-person and will hopefully inspire you to use this time to add more play to your every day. Here are a few ways you can start this work tomorrow (or Monday!):

1. Get to know the players in your space, including what THEY like to play.

The universal language of play is a low-stakes way to communicate and connect and a much more fun way to learn! If you haven’t already, ask your learners AND your colleagues to share what games they like to play when they aren’t in class. There will likely be the common refrain from games on the ballfield to those on the keyboard, but listen closely because what they tell you is not only who plays what games but why they play and with whom.

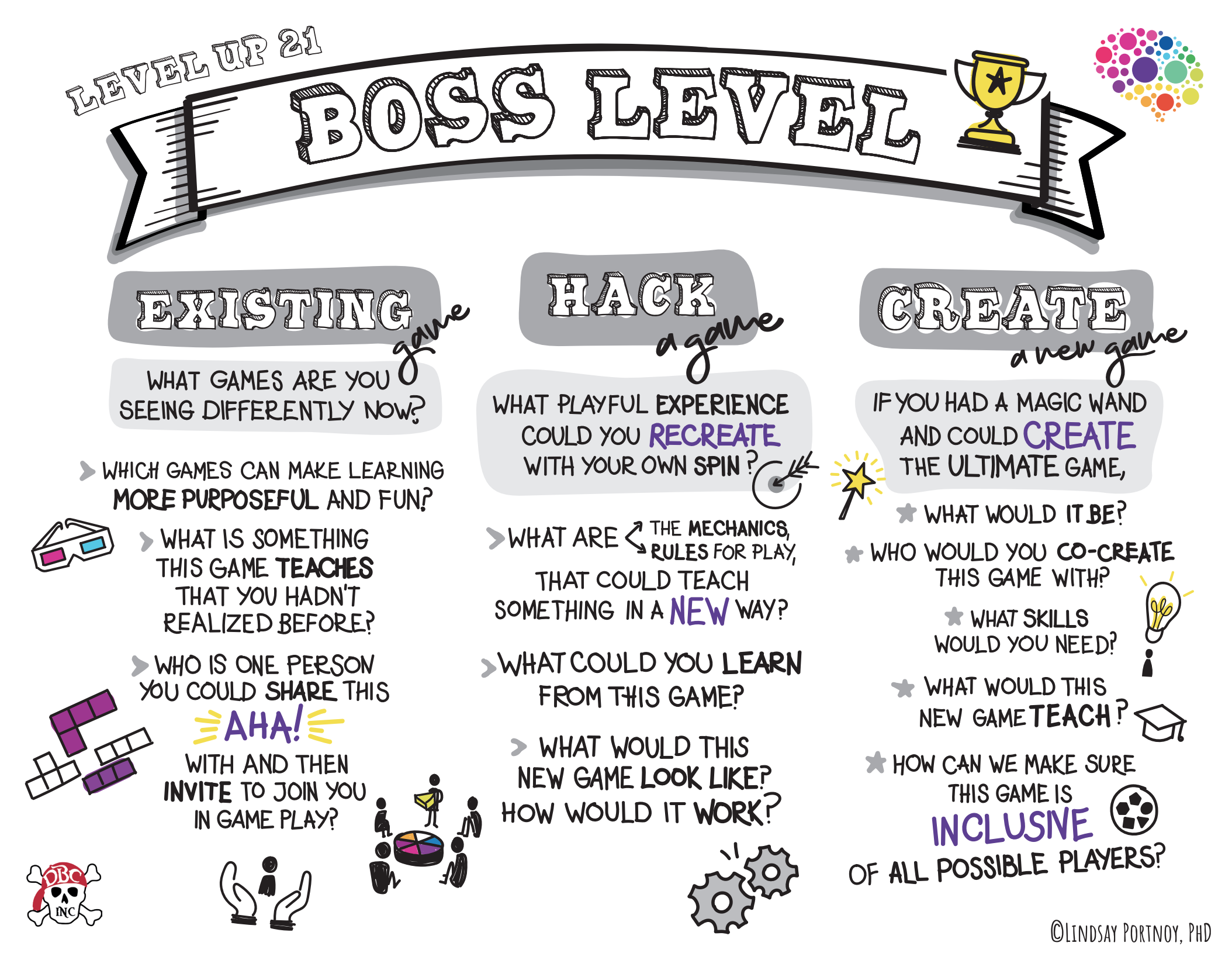

You can even borrow the image from Level Up 4 here to get started. And if you’re feeling particularly adventurous, you might ask them to bring those games into class and see if they can’t find ways to bridge the joy of play with the joy of learning. How can your students use the Zoom whiteboard to play a game of Pictionary or use MinecraftEdu to build a replica of ancient Egypt? Learning through play makes it more fun, less stressful, and invites that natural collaboration that each of us yearns for in learning and in life.

2. ...and don’t forget to introduce YOU!

We’re all inundated with messages about Maslow before Bloom, but how many of us take the time to really get to know our colleagues or are invited to share unique attributes of our own lives? A dear friend and colleague, Chris Unger, likes to recall the story of a time he stopped a PD just as it began and abruptly asked the teachers in the room: what do you really care about? What are you doing when you’re not here at school?

The mood in the room changed entirely, but the story doesn’t end there. The school has reenvisioned their curriculum by including novel courses inspired by the teacher’s passions, from “Being Politically Active” to “Bad Sci-Fi Science” where students learn important concepts from scientific inquiry to identifying issues that matter most to each student. Built off the passions and expertise of the faculty, the school re-envisioned how teaching and learning takes place. What a powerful way to help teachers and students see themselves every day.

3. Share the gameboard by using The Force: Dreams, needs and shares

What are the hats you wear? How do you communicate differently in those different roles? As you think about the many hats you don in your life and how each one requires you to communicate in different ways, consider the other players in your space who have a different voice, different experiences, and different goals. Sharing the gameboard means knowing about who is in your space and being clear about what supports you need and what superpowers you can share so that everyone is met with opportunity.

Pre-COVID, when I could run PDs in person, one of my favorite activities and the one that was often loudest and most generative, was called Dreams, Needs and Shares. It’s a simple exercise based on a single question: What is a pie-in-the-sky dream for your work this year in the classroom?

Based on the dream statement, I’d ask you to consider: What do you need to attain that goal? And lastly, I’d ask: What superpower do you have that your colleagues may not know about but could be valuable to them? Sharing everyone’s dreams, their needs to make those dreams a reality, and the shares that reveal the potential within the room is the real warp zone to innovation in education.

Together we have everything we need to solve even the most complicated problems in our world. The only question that remains is: Are you game to begin?

…

Read the entire guest post on the Dave Burgess Consulting blog here: https://www.daveburgessconsulting.com/2020/10/07/is-monkey-business-the-most-important-business/